Growing up as a second-generation immigrant daughter of Vietnamese refugees, there could’ve been lots of opportunities to get teased by my peers at school. I could’ve dressed funny, looked different, sounded funny, and brought a stinky, gross lunch to school.

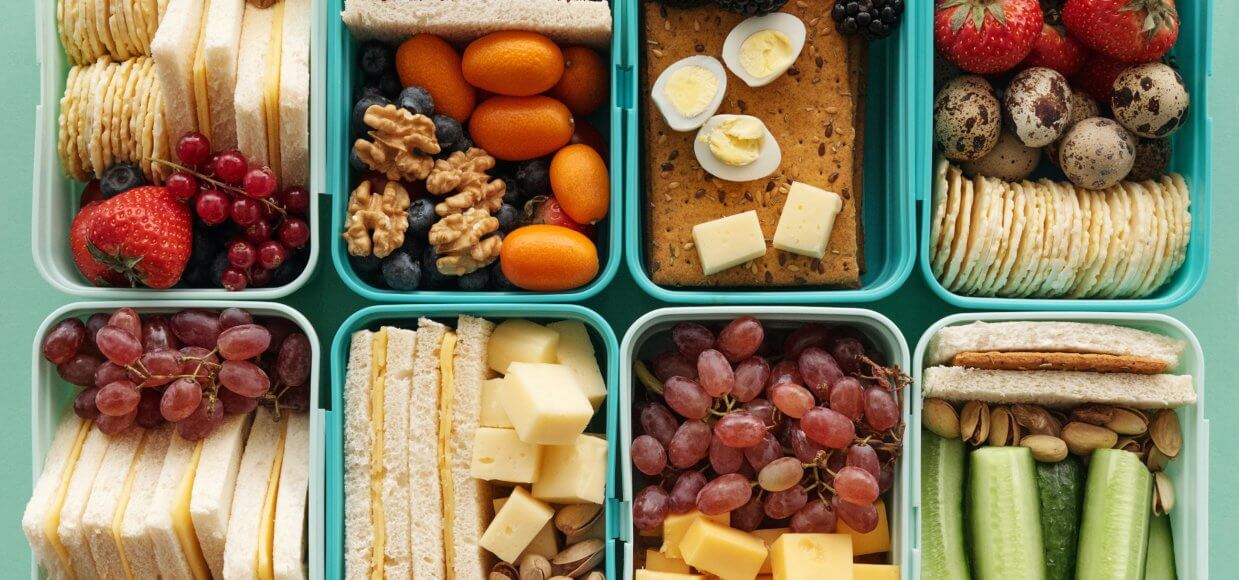

But unlike dozens of immigrant children who have written essays on the topic, I never experienced the horrific “lunchbox moment.” While other children of immigrants were teased for unpacking their spam and eggs or their chowmeins that look like worms, my father sent me to school with nacho cheese Lunchables or ham and cheese sandwiches with a bag of sliced apples and a juice box. My mom dressed me in Old Navy overalls and put me in dance, ice skating and gymnastics.

Growing up, my parents did a good job of assimilating me into the American culture and life. As a kid, this gave me the advantage of feeling like I belonged. Without a “weird” lunch and proficient English, I fit in pretty seamlessly. I easily made friends at the playground, enjoyed dance competitions, and went to birthday parties on the weekends. Besides possibly looking different, I was considered “normal” just like all the other kids.

But now as an adult, I realize that all that time I spent trying to fit in with homogenized white bread lunches made me lose a piece of myself and my identity.

For so many immigrant families, fitting in means giving up what should be celebrated.

My parents both emigrated from Vietnam in the late 1970’s to escape the aftermath of the Vietnam War. Both of them are considered “Boat People.” As the name implies, they were 2 of about 700,000 people who fled the country by small boats. Like so many tragic stories of the time, my dad made the trip by himself, leaving his entire family behind. My mom, who immigrated around the same time, was able to come with a few of her siblings.

After taking a boat from Vietnam to Indonesia and Malaysia to a refugee camp—a harrowing journey that included avoiding pirates—they were able to reunite with distant family members in California. My mom ended up in Modesto and my dad in San Bernardino. Eventually, they learned English, went to community college and found great jobs. They got married, had my older brother and I, bought a house, got a Mustang—my mother’s dream car—and altogether lived what some would consider the normal “American Dream.”

Around the time I was born, my dad was able to sponsor most of his family who were still living in Vietnam to come live within America. So, like many immigrant families, I grew up in a multi-generational home in the Bay Area with my parents, brother, Ye Ye (grandfather), Ma Ma (grandmother), Tai Ma (great grandmother), my aunt, my uncle, his wife and their child. As a kid, I was exposed to much of my heritage, which is Vietnamese and Chinese. Although my parents are from Vietnam, my family lineage roots back to China. I grew up surrounded by such a vibrant dual culture and both native languages. Vietnamese or Chinese home-cooked meals were always on the table for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

It wasn’t until my brother started Pre-K and struggled to socialize with the other kids that any of that was a problem. My parents, with help of a medical expert, concluded that it was normal for him as this is a result of being raised in a multilingual household. My parents decided that they didn’t want me to have the same experience, so they swapped out Cantonese for English, and spoke Vietnamese only with each other.

Over the years, I’ve learned a little bit more of my parent’s story, their journey, their struggles in a new country and their grit and determination to succeed. I’m extremely proud of my family, our traditions and my background. I want to continue to celebrate the culture I inherited and the food I grew up eating.

Food is a big piece of a person’s identity, and repressing that comes with unfortunate consequences.

On a personal level, I was robbed of my own identity as a daughter of Vietnamese immigrants. American holidays such as Thanksgiving were celebrated with my mother’s extended family by sitting around the dinner table with turkey, ham, mashed potatoes with gravy, macaroni and cheese, green beans, salad, cornbread, and apple pie.

My aunties and uncles would speak with my cousins and me in Vietnamese, and we would respond in English. I spent a large part of my life trying to fit in and be normal, without taking into consideration that I am American—Asian American. Up until a few years ago, my Cantonese was pretty broken, and I struggled to even have conversations with my grandparents. I barely understand Vietnamese anymore, which makes eavesdropping on my parents more difficult. There are so many traditional dishes that I used to eat but never learned how to make.

Over the past year, with the rise in AAPI hate crimes, I started to reflect on my life and my own experiences. I won’t get into the details but like most Asian American women, I struggle to be seen, to be heard, to be taken seriously, and I must be good at math because I’m Asian – newsflash, the most classes I failed were math classes. But as a child, I had my moment to be loud but was unintentionally robbed of that experience—that lunch box moment. That moment to be seen and not just blend into the background.

I’m relearning how to write in Chinese, have Vietnamese or Chinese dinners at my parent’s house on Sundays where they practice Cantonese with me, and spend every Lunar New Year in the kitchen with my aunt and uncle learning how to make traditional dishes. As we reassimilate to our new normal post-Covid and kids are going back to school with their lunches, I hope that being “normal” isn’t something we strive for any longer and kids can be proud of their lunch.

Lily is the Director of Business Operations at Off the Grid. She designs and executes internal business processes for the Catering and Community Care business lines to empower local food communities to thrive by connecting creators to guests seeking comfort and care. She is a Bay Area native, an avid reader, and on a mission to find the best brunch spots in town.